Responsible AI Photo Restoration

If you’re anything like me, you’ve got boxes of old family photos, many of which have seen better days. Water damage, fading, colour shifting, tears (both the torn kind and the crying kind), mysterious spots and coffee rings – the ravages of time spare no photograph. You’ve probably wished you could wave a magic wand and restore them to their former glory.

That magic wand may be here in the form of AI-powered image restoration tools. What used to take months to learn, and hours of painstaking work to apply, can now be accomplished in minutes.

But great power comes with great responsibility.

Traditional Solutions: From Darkroom to Digital

Photo restoration isn’t new, but its dramatic evolution from the darkroom to generative AI requires a responsible approach.

Since the dawn of photography, people have been modifying and enhancing photographs. In the darkroom era, skilled technicians could perform minor miracles with the right chemicals and techniques.

I was a darkroom technician for my local newspaper in high school. It was a highlight of my youth to learn the techniques for adjusting contrast and exposure, or to highlight the important parts of a photograph to help tell a story. Darkroom pros could even composite multiple negatives together to create a better—or at least different—photograph than that captured by the lens. Darkrooms came with their challenges though. The techniques took lots time and effort to learn, not to mention the money for the equipment, chemicals, and film.

The digital revolution brought us Photoshop in the early 1990’s and democratized photo restoration for anyone willing to invest the time to learn it and the money to buy it. When it was first released, Photoshop cost about US$700. And, you didn’t need a darkroom!

Suddenly, we could remove scratches, adjust colors with precision, and even reconstruct missing portions of images. Although, like the darkroom techniques that came before them, these tools required substantial skill and practice to master. Before you could reliably restore a single old photo, it often took months to learn the basic techniques, then hours to apply them to each damaged piece of family history found in the old box of photos.

A positive thing that darkroom and traditional Photoshop techniques had in common was that they only modified the specific aspects of the images that they were applied to. If you changed the contrast, you only changed the contrast. If you decreased the exposure, you only decreased the exposure. Nothing more, nothing less.

AI Photo Restoration Changes the Game

Traditional techniques only modify the specific parts of the image you choose to edit. AI tools, on the other hand, generate an entirely new image.

For example, when you ask it to “remove the scratch through the bouquet in this wedding photo,” it generates an entirely new image, pixel by pixel, based on a combination of:

- The image you provided it

- The prompt you gave it

- The training it has received on billions of other photographs

A year ago, modifying an existing image was more fun (and frustrating) than functional.

The release of ChatGPT-4o image generator in March of 2025 greatly improved on this, even though it still has a nasty habit of modifying portions of the image that you didn’t intend it to. For example, tweaking the contrast of an old photo of grandpa’s barn could result in the removal of the weathervane from the roof or the addition of a new tree to the backyard.

Google Ups the Ante with Nano Banana

Gemini 2.5 Flash Image was released by Google on August 26, 2025. It was stealthily released a few weeks earlier for testing and benchmarking at LM Arena under the codename Nano Banana. Whatever it’s called, this new image model represents a huge leap forward in AI-based image restoration.

Gemini 2.5 Flash Image is much better than earlier AI tools at preserving facial characteristics and historical details when modifying visual elements like contrast, exposure and sharpness. What once took months of learning and hours of effort in Photoshop or the darkroom can now be done in minutes with a simple text prompt.

While Gemini Flash Image still makes mistakes, the improvements in detail preservation from original to edit are frequently amazing.

Despite some predictable backlash from the genealogical community, AI-based image restoration has a lot going for it. It is easy to learn, fast to use, and relatively inexpensive. Plus, it is now good enough to suit the needs of many people.

Fast, easy, and cheap are the holy trinity of consumer software. So, love it or hate it, AI-based image editing is here to stay.

AI Restoration is Different From Photoshop

Large language models can’t selectively edit a portion of an image. Instead, they generate every pixel in an image when you ask it to make a change to the original, no matter how small the change is that you wish to make. Even though AI tools can now preserve details between the original and edited versions better than they used to be able to, the possibility for errors remains high.

Historical images are often cracked, torn, or faded. The result is that some details can be difficult to interpret or missing completely. AI tackles this challenge by making “educated guesses” about the details that it can’t see by comparing your photo to the billions of photos in their training data. This feature, which is so appealing for casual photo enhancement, is a problem for historical research and genealogy.

- The barely visible pattern on great-grandmother’s dress? The AI will complete it based on patterns it’s seen in other photographs from that era.

- The faded building in the background? It’ll sharpen and enhance it based on architectural styles it’s seen before.

- The hair style that’s difficult to see in the overexposed photo? The AI will select one from the hundreds of styles that it has been trained on.

Most of the time, these guesses are remarkably good. Gemini Flash Image is nothing short of amazing at preserving “genealogically relevant” elements of a photograph – faces, clothing styles, and general period accuracy. But guessing is still guessing. These guesses can introduce details that were never there and can remove or change details that were.

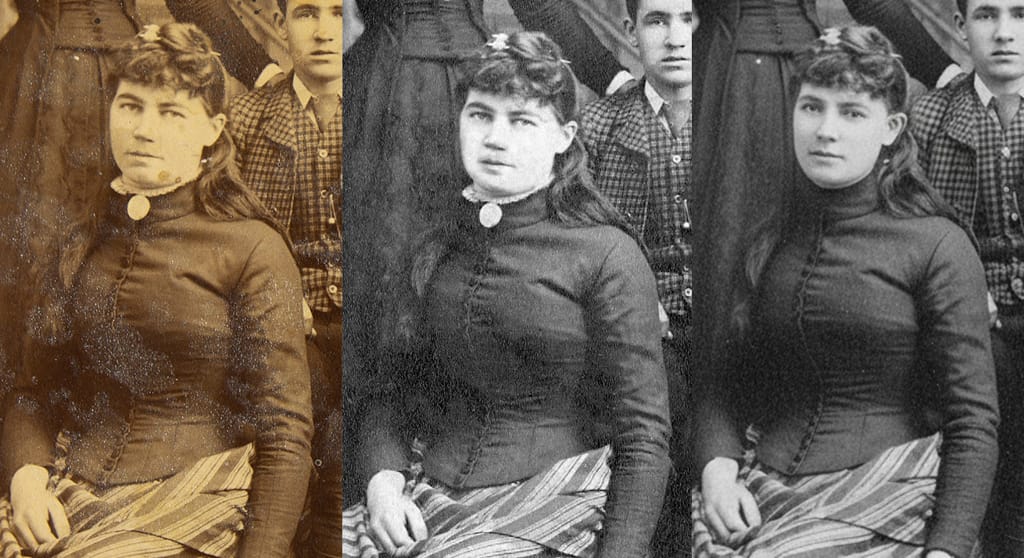

The photo below is a cherished heirloom in my family. It is the only known photo of my great grandfather, Charles Thompson, and his siblings. You’ll notice though, the photo shows its age, with a variety of issues due to yellowing, dust, scratches and spills.

Image 1. Children of James Thompson and Catherine Mulrooney, Abt. 1885. Likely taken in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Left to right. Back row standing: Mary Anne Thompson, Sarah Catherine Thompson. Middle row seated: Charles James Thompson, John James Thompson. Front row kneeling: Margaret Thompson, Possibly Mary Elizabeth [Last Name Unknown] [possibly adopted], Agnes Thompson. Unedited copy of original photograph held in Mark Thompson’s personal collection.

Image 2. A comparison of edits on a closeup of Margaret Thompson. Left: Unedited crop from the original. Middle: Edited in Photoshop, about 2020, for black and white conversion, contrast, and spot removal. Right: Modified in Gemini 2.5 Image Flash 3 September 2025 for black and white conversion, contrast, and spot removal, which also altered her facial features and the neckline of her dress.

While Gemini does a remarkable job of restoring many aspects of this damaged photograph, Margaret Thompson’s likeness was materially altered. The result, shown in the rightmost version of Image 2 above, resulted in two genealogically significant changes. Take a close look at her face and neckline across the three images to see what changed. First and foremost, her face was changed enough that she is no longer recognizable as the same person. Second, Gemini removed the brooch and ruffles from the neckline of her dress. I believe Gemini was confused by the number of spots and marks on the photo in this area, and had difficulty distinguishing the contents of the image from the damage on it.

Because generative AI editing tools, like Gemini and ChatGPT, have the potential to materially alter images in unexpected ways, it’s important to disclose when you use them.

Disclosure

This brings us to a crucial principle that’s as old as genealogy itself: documenting our source, the source that it was derived from, and disclosing the changes that were made between the two.

Genealogists have long followed this principle with written records.

- When we abstract information from a longer document, we make it clear it’s an abstract, not a full transcription.

- When we transcribe a difficult-to-read document, we note uncertain words with a [?] rather than guessing.

- When we translate a document from another language, we note that we created a translation of the original, and which language the original document was written in.

This disclosure principle applies to image modifications as well. This is increasingly important in the age of AI, especially:

- When we tweak some visual characteristics of an image we say something like, “lightly edited for tone and contrast.”

- If we strongly modify an image for research purposes we could say something like, “contrast greatly enhanced to improve the visibility of the sign in the store front”

- When we Photoshop in an image of the sibling who wasn’t able to make it to the family reunion, we say “composite image, sister Sarah added on the left because she passed away earlier that year from consumption”

Obviously, not all image modifications are created equal. Some, like the “lightly edited” example are not genealogically relevant. The “sister Sarah” example could easily result in conflicting evidence about when Sarah lived.

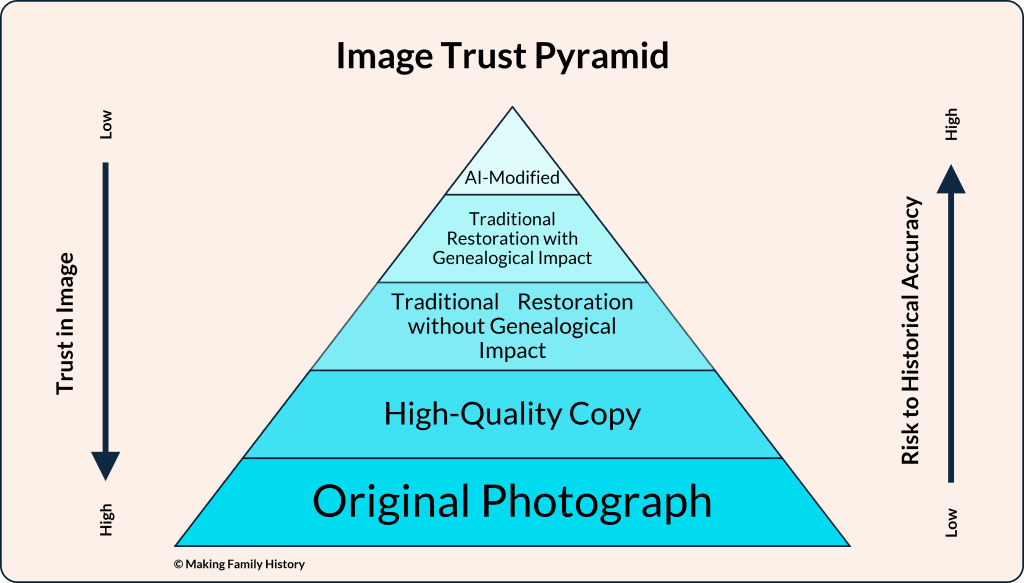

Here is the model I use when analyzing photographs for genealogy research.

Image Trust Pyramid

Each level up this pyramid represents a step further away from the original photograph, resulting in an image that is less trustworthy for genealogical research than the level below it.

This isn’t to suggest that less trustworthy photos aren’t useful, or that modern tools shouldn’t be used to modify your images. The key is disclosure. When you disclose the modifications you’ve made, you inform viewers how much they can trust that what they are seeing was captured by the camera in the first place.

Figure 1: The Image Trust Pyramid shows the relationship between image modifications and the risk of using the image as a sole source for genealogy research.

1. The Original Print

The physical photograph is the foundation of the pyramid. It is the most trustworthy version. In genealogical terms, it is the “original source document.” The original print almost always provides additional evidence that can’t be gleaned from a copy.

2. High-Quality Copy

An unedited, color balanced, high resolution copy of the entire front and back of the photograph is the next most trustworthy version.

3. Traditional Restoration without Genealogical Impact

Images modified with conventional darkroom techniques or image editing software, where the modifications do not impact genealogically or historically relevant characteristics of the image. For example: contrast, brightness, scratch or dust removal, resolution change, image size, etc.

4. Traditional Restoration with Genealogical Impact

Images modified with conventional darkroom techniques or image editing software, where the modifications impact genealogically or historically relevant characteristics of the image. For example; colourization, cropping, compositing, object removal, person removal, etc.

5. AI-Modified Image

Images where generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT, Gemini, or Grok were used to modify or enhance any aspect of the image. AI-Enhanced images are at the peak of the pyramid, furthest removed from the original source, and should be trusted the least.

Describe Your Images

How do we put the disclosure principle into practice? Here are three common approaches that work well. The method you choose matters less than the disclosure itself. Future family members and researchers will be forever grateful that you took the time to explain what they’re looking at, how it relates to the original family photograph, and how they can find it if they need to.

1. The Side-by-Side Method

The simplest approach is to share both versions – the high-quality copy and the modified version. When sharing them, include a clear description of the image, and the modifications that you made.

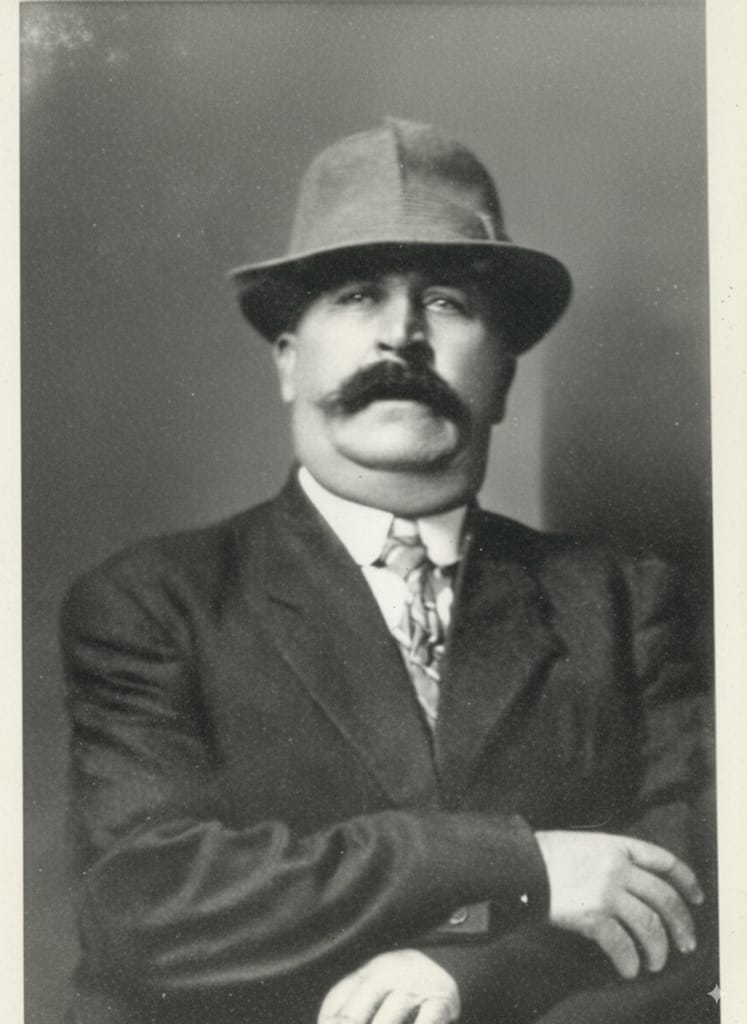

Image 3. Thomas Shields, abt. 1890, likely Toronto, Ontario. Left side scanned from original by Paul Murphy, 2008. Right side modified with Gemini 2.5 Flash on 3 September 2025 for crack repair, colour correction, and spot removal. Original held in Mark Thompson’s personal collection.

This gives casual viewers and future family history researchers an opportunity to appreciate both the original and restored photos, as well as the context that they need to interpret what they are looking at.

2. The Detailed Description Method

For situations where showing both versions isn’t practical, include a detailed description of the modifications made in the image shown.

Image 4. Neil Charles Thompson. Likely a school photo taken in Nipigon, Ontario, Canada about 1955. Scanned in 2004 by Kyra Thompson. Edited in Photoshop by Mark Thompson in 2007. Edited for repair of large crack across face, brightening of overall image, and dust spot removal. Original held in Mark Thompson’s personal collection.

3. The Citation Method

Formal genealogical work uses citations based upon an extended version of the Chicago Manual of Style, which is described in glorious detail in Elizabeth Shown Mills’ book Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace, 4th Edition.

While a lot of ink has been spilled (not to mention the frustrations howled at the moon) on the how to create citations, the goal of citations is fairly straightforward. Help readers understand what they are looking at and how to find it again. In order to do this for original photographs, include as much of the following as your evidence can support:

- What is in the photo (who, what, when, where, why)

- Who took the photograph

- The type of photograph (tin type, 35 mm, etc.)

- Where the original photo can be found (or was found)

If the digital image being shown was modified from the original, describe what was done:

- What modifications were made

- Who modified it

- What tools were used to modify it

- When it was modified

It is good practice to combine information about both the original and edited versions together into a single layered citation. This gives readers a crisp description about the digital image that they are looking at, the original photograph that it was derived from, and the changes that were made between one and the other.

For example, below you’ll see the AI-modified image of my great grandfather, Thomas Joseph Shields. Although the image only shows the modified version, the layered citation describes the modified version, the original photograph held in my collection, and the changes that were made between the original photograph and the image shown.

Image 5. Digital image of original photograph of Thomas Joseph Shields, modified by Mark Thompson using Gemini 2.5 Flash Image, 3 Sept. 2025 (modified for crack repairs to lower half, correction of age-related yellowing, and removal of spots and dust); Original photograph, ca. 1890, probably Toronto, Ontario, Canada, privately held by Mark Thompson [address for private use].

Responsible Stewardship of Family Photos

How you manage your family photo collection can have a big impact on how easy it easy to follow these guidelines. Use this essential reference guide to help you preserve the legacy held within your family photos—whether original, digitized, or AI-enhanced:

1. Make a high-quality digital copy

Make a 600 DPI scan (or 12 MB photographic copy) of your historical family photographs. If the frame or album allows, copy the entire photograph out to the edge and the back of the photograph if there are any markings on it.

2. Preservation is Key

Store high-quality copies in a place, or in a way, that makes it clear that they are never to be modified. When you want to share a modified image with someone, make a duplicate of the high-quality one to ensure the original scan is never altered.

Protect and preserve your original photographs. Backup your high-quality digital copies. Keep one of your backup copies outside of your home. Share your high-quality copies far and wide throughout your family. Make plans to pass your original photographs to the next Story Keeper. These actions will help ensure that your efforts to preserve your family’s history aren’t lost when you pass on.

3. Share What Changed When You Share the Images

Knowledge of even minor tweaks will help future researchers understand what they are looking at. “modified using AI” is better than “edited,” but something like “Enhanced contrast using Gemini Flash Image, 5 September 2025” is better yet. Over-communication about what and how you modified the image from the original is better than under-communication.

While Facebook posts shared with family don’t need as much detail as formal genealogical research reports, disclosure is always appropriate. The point is to preserve trust in the images that you share.

4. Preserve genealogical accuracy

Unless your editing goal is purely artistic, prioritize the preservation of faces, clothing, and period details over aesthetic improvements.

5. Save your prompts

If modifications were made using AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini, save the prompts you used for future reference. Tools like OneNote, Word, Google Docs, Excel, Google Sheets, are all great places to store and retrieve your prompts. This will not only help you remember what you did, it will also help you get better with your prompting.

6. Verify, verify, verify

Whether you use traditional or AI-enhanced editing methods, carefully compare your modified image against the original to identify any unintended changes.

Experiment Responsibly

I encourage you to experiment with these tools now. Pick a damaged historical photo from your family collection that you’ve always wished looked better. Try restoring it with different tools – Gemini Flash Image, ChatGPT, or whatever emerges next week from your favourite AI company.

Try different approaches to prompting. Follow the best practice I’ve outlined above, documenting your experiments carefully. Try new things that no one has dreamed of yet. Keep track of your successes and your failures. Remember, you will learn more from your failures than you will from your successes.

When you share your results, include both the original and restored versions with clear explanations of what you did. This greatly reduces the possibility that your family, or future researchers, will misinterpret what they are looking at.

Conclusion

We’re not just editing images – we’re stewarding our family history. Even as these tools approach near-perfect editing capabilities, trust in the final result will be improved when we disclose the changes we made. It’s not about choosing between traditional methods and new technologies; it’s about combining the best of both with integrity.

Our ancestors trusted us with their photographs. Future generations are trusting us to preserve and pass them along accurately. By disclosing our work clearly and completely, we honor both trusts. These tools offer incredible potential to engage the younger generation; those who might otherwise ignore a box of faded photos.

That magic wand you wished for? You have one now. Use it wisely!

Thank you for this great post. You make some excellent points. Some additional information that I feel should be included is not only the type of photo, CDV, Cabinet Card, etc., but also the length/height, width, thickness, of the original image; whether the digital version was digitized from a negative, print, or slide; if from a negative, specific brand and type of film, if known. Thickness of glass for glass negatives and of cardboard for CDVs can be a clue to date era of the original’s production. Sheet films 4×5 inches or larger have distinct patterns of notches in the upper right corner to tell the darkroom tech who was developing it which specific type of film it was. Tables or charts are available to identify film types. Roll films of any format normally have the manufacturer’s name and code name or film number printed near one or more edges, outside of the image area. Knowledge of the type of film used can lead to finding when a particular film was first marketed and when its production ended, as found in various charts online, thus providing a clue as to the range of dates an image could have possibly been made. For recent photos, circa 1950 and later, if the photographer is known, it may be possible to learn the specific make(s) and model(s) of lens(es) used or specific techniques used for each photo, information generally included in EXIF metadata on digital cameras. Some photographers recorded such data manually on paper, especially when they were learning photography. A free program, AnalogEXIF, available online, lets that data be included with digital images.

Art,

I agree… it seems like the things to track are endless. In the end, the things that matter are the things that should be tracked. And, the things that matter most are different for everyone. Thankfully modern cameras take care of most of the important stuff for us with the EXIF metadata. As to ancient family photographs, I have rarely seen any technical documentation about a photograph (I wish!). Usually this is only documented by people who were professional photographers. I’ve even heard this shortcoming lamented by big production scanning facilities. Even though it is their business to understand their collections, they often don’t have little metadata about how their own reproductions were done. sigh. And, if we ever make a copy or an edit, it can all be lost! So, this is why it’s so important for us to document the history of our images and what we’ve done to them.

This is great, Mark. Very important information. I appreciate the details.

You’re very welcome Chris. This one was a lot of fun to put together.

Excellent! Thank you for taking the time to organize this information and share it.

Thanks Carol. Much appreciated!